Somehow my mother had gotten herself out of bed and down the four steps to the main level, taken her walker out the door and to the rose trellis at the side of the house. My stepfather found her sitting on the seat of the walker, fuming. Hours later she was back in bed but I could see smoke still rising all around her.

“Two of them, just standing there, chewing on the Paul Scarlett and the Irene of Denmark, and the Peace and Aloha were in shreds,” she snarled. “If I had had my cane…”

I looked at my stepfather and he nodded in agreement. If she had had her cane, she would have fallen over. I could feel my ex, who was standing in the doorway, was thinking the same thing. Having elderly parents in the same city had made us allies, almost a team.

“I can remember when this was all forest,” I sighed. “We used to have Sunday School hikes down here. We’d see the deer, hear them in the bush by the creek.”

I sat on the end of the bed, even though I knew she would consider that an infringement of her territory.

“That was then,” she glared. “It’s that damned conservation area.”

I didn’t remind her that the conservation area had been one of the reasons for moving in. She’d just start in about how I lived downtown and had no neighbors. All of her friends on the street were gone, had retreated to retirement condos where they played bridge and went on bus trips to casinos. Mama just did crosswords in ink all day, and since my stepfather could still cope with the house and her, they were staying put.

“You’re as much of a pain in the ass as the deer,” she muttered.

I had a vision of red cola cans growing on the trees and the crunching sound they’d make as I chewed on them. I sulked on the way back home, resenting the money spent on gas for the hundred mile trip on a Saturday afternoon when we could have been on the beach or in the canoe.

***

The next time we went, Mama was still irate and making illogical threats. Some elderly woman had beaten a fawn to death in a southern state. I hoped she hadn’t heard about that. I didn’t want her getting any ideas.

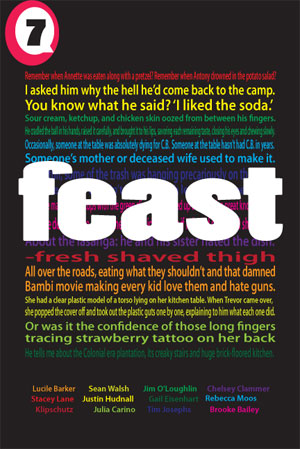

“When has a deer ever done anything good?” she asked. “All over the roads, eating what they shouldn’t and that damned Bambi movie making every kid love them and hate guns. We need a deer cull.”

There was gong to be one in a bog in a city a few hundred miles away because the deer were getting caught on fences and were unable to find enough to eat. I was upset about that but the deer here were different, and if roses for breakfast was an option for them, I could go along with it.

“They’re vicious with the roses,” my stepfather nodded like a backbencher agreeing with the party leader. “I just missed them this morning.”

“What have they ever done for anyone?” my mother asked, her eyes glowing like a predatory beast smelling meat, even in the dark, always curtained bedroom.

“Do you remember the doeskin jacket you had when I was little?” I asked.

“You were always little,” she sneered, though I felt like the circus fat lady next to her.

“It was russet,” I reminded her.

She looked blank.

“You had it from the time I was three until about when I was eight.”

I didn’t remind her that she had promised it to me when I grew up. I never had grown up, which might be a good thing. If I was an adult, I might assign blame. This way she always had the upper hand. I surrendered my adulthood every time I walked in her door and it was too late for her to recognize it now, too late for me to claim it.

“Oh, that old thing,” she said dismissively.

I remembered the coat. It had glowed like a rusty sunset, an auburn that shimmered. It was soft, delicate and I always wanted to put my face against it. Sometimes she had let me sleep on it in the car, its softness so velvety and comforting on the bumpy back roads we always seemed to end up on. The jacket, which was car-coat length on her, had disappeared, perhaps in one of the endless moves to another state, another country, another province, a different job or company. I looked at her and could see that she could remember it, but that she didn’t want to.

***

My mother died at the end of June and we held the funeral in July. My stepfather wanted to make sure there was a vase of her Paul Scarlett roses in front of the urn. The vase was to sit on my daughter’s lap on the way to the funeral. We were heading out the door when the car alarm went off in our borrowed car. This set off Mama and my stepfather Ricky’s car alarm as well.

“Mama’s ghost telling us to get this show on the road,” I said.

“No,” my stepfather said, gazing over to the conservation area. “One of those damned deer did it. Bumped it and set it off.”

I couldn’t see a raised white tail out there, but I shrugged and let it go. We hit the tiny road that wound around the clogged highway that would get us to the funeral home. I wasn’t paying much attention, but all the traffic suddenly stopped. I looked up.

“Holy cow!” I heard my younger son say, but it wasn’t a cow.

I had missed the herd of five deer gamboling slowly across the road in front of the car. I was known as the deer spotter of the family, but I hadn’t been fast enough to get a glimpse of them.

The car alarm went off again when the urn was brought to the hearse. It set off a few other alarms in the parking lot. Some people got a 21 cannon salute, but Mama had eight car alarms.

***

We went back to the city after the funeral and sat on the beach, watching a July sunset that was too golden for the color of the suede coat I still dreamed of. I knew that I would have to go back to help my stepfather clear out Mama’s things.

I went on the bus the next week and Ricky picked me up at the local plaza, an uncharacteristic glare clouding his face.

“There are thieves in the cemetery!” he said.

I had visions of grave-robbers.

“They stole the flowers I put out last night.”

I knew he was going to the cemetery too often, not accepting that it wasn’t really her there, just the ashes.

“I put fresh ones there this morning in the little brass vase attached to the marker,” he said. “I’m going to watch and see what happens.”

We drove the long slow circular way around the cemetery to where my father and grandparents were buried. And now Mama. For her funeral, their flat markers had been covered. I used to go to the cemetery every once in a while before Rosh Hoshana and mumble a few fractured prayers for my relatives, but this had become more infrequent over the years.

***

We walked to the still fresh grave, the new sod a too bright shade of green against the water-starved July grass around it. There were no flowers in the little brass vase, but there were stems on the bronze marker below.

A cemetery employee rolled by on a riding tractor and Ricky hailed him.

“Look, someone has been stealing the flowers from my wife’s grave!” he told the man.

I looked around and none of the other graves had flowers. Ricky bent down and picked up the stems covering Mama’s name.

“They even cut the tops off them!”

I knew before the man started to speak, and I was biting my lip. I didn’t know if I would laugh or cry.

“I’m so sorry, Mr. Bohls,” the man said. “You must have put roses there.” He pointed to the forested area under the rocky escarpment that defined the city. “It’s the deer. They come right over from the conservation area and some days I’d swear that they already have petals on their nuzzles. They must have a route.”

Ricky took the flowers later in the day from then on, sat on the polished black marble bench a few feet away to scare off the intruders. I was willing to believe that the deer knew where the day old outlet was when they came the next morning.

Another generation was having problems with the deer, as well. My oldest son was a long distance trucker. He admitted that he had hit three deer in the past thirty months. His fellow drivers were beginning to refer to him as “the Deer Hunter.” In some states the driver has to pay for deer removal.

“One guy just left a big buck on the road so he wouldn’t have to pay. Who knows what was coming along next? If it was a little thing like Annabel drives…”

I thought of getting him three of the leaping deer decals that were available at our local automotive store, but he sold the truck and went into engine repair.

The last time we visited my stepfather there was a sign up at the intersection to the subdivision and the back road to the cemetery. It was written in black marker and coated with clear plastic.

SIX DEER HIT ON THIS ROAD

FIVE SERIOUS INJURIES

DRIVE SLOWLY

“Did you see that?” I asked but everyone else had missed it.

***

Now, when I drive home on the back road, I make a point to go at twilight. That’s when the deer come out to feed on the tender weeds growing in the ditches by the road. I drive slowly, and with care. But I’m not afraid. The deer know which side I’m on, lift their heads and nod.

Enjoy the roses, I tell them.

Lucile Barker is a Toronto poet, writer and activist who has been writing since she first swiped her grandmother’s Waterman fountain pen and her mother’s lilac ink. The time spent in the corner gave her more opportunity to write. Since 1994, she has been the co-ordinator of the Joy of Writing, a weekly workshop at the Ralph Thornton Centre. The group now has a Facebook group and almost 150 members, some of whom actually do the assignments. She has had eighteen acceptances of poetry, prose and creative nonfiction so far this year, but this is a small percentage of what has been submitted. OCD can be a good thing… With an unlimited supply of postage and chutzpah, there is the possibility of having the largest collection of rejection slips in the world. However, there are no plans for an exhibit of these at present.