I’d become confused, as a supposed humanitarian, about my place in the human family. I started walking to work, even though it was South Sudan, even though it was forbidden. I’d flown across the world and all I’d done was sit in air-conditioned trailers behind concrete walls topped with barbed wire that protected me from dying people. My confusion began to feel dangerous, more even than bucking protocol, so I walked.

Feet and lorries kicked the dried out, unpaved road into a hovering powder that turned the air dense all day long and it felt good to add to that unfiltered mess instead of just passively breathing it. It was on that road that a little boy wandered up to me one morning, wearing a tattered oversized t-shirt that hung past his knees. He hit me with a pearly white blowtorch smile and started singing a little song of his own creation that went, “Kwadjo! Kwadjo!” which meant “foreigner” or “whitey,” depending on who you asked.

The little boy held his hand out for me to take and here was the catch: the scalp of the cutest little boy on earth was covered with oozing sores and swarming with flies. His precious little head of curly hair was yellow from malnutrition, and judging by his exaggerated head-to-body ratio, his parents had already started redistributing his share of food to healthier siblings deemed more likely to live. This is something that happened when hard times grew impenetrable.

The Center for Disease Control referred to Southern Sudan as “a living museum of infectious disease,” and the little tyke obviously had more than his share. That said, all he wanted to do was hold my hand as he walked to school.

This was the most direct opportunity I’d had to know just how willing I was to get my hands dirty, so I enveloped his hand in mine and watched him toddle alongside me singing his song. When we passed the school, he turned and ran through the gate without saying goodbye.

I continued on to the UNICEF compound, sat in the processed cool of my air-conditioned trailer, and slathered ethanol sanitizer all over my hands, up to the elbows, and if that isn’t a metaphor for aide work then I don’t know what is.

***

“It’s the kids that are really the worst part of the job.”

I’d told Stuart about the little boy during our afternoon smoke break. His response caught me a little off guard, seeing as how he was a lawyer working in the Child Protection Division of UNICEF.

“You just can’t win with the kids out here. There was one time I was up at a camp repatriating child soldiers. This one kid couldn’t have been a day over twelve. He’d been in the camp as long as I had, and none of the local staff had got anything out of him about where he was from.

“So finally I sit him down, buy him a soda and get him talking and he let’s slip a few details and I figure out where his village is. So we stick him on a plane, fly him a couple hundred kilometers to the south and the crew on the other end sees that he’s returned home. Great heartwarming story, right?”

Stuart flashed the grin of a dog greeting its owners after getting in the pantry, not unlike the one he wielded on women. It was the grin that earned him the nickname, “Greasy Stu.”

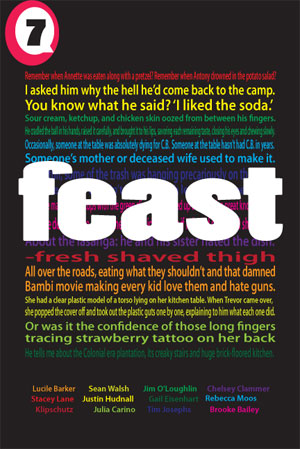

“Two months later, I’m walking through the camp and I see the little bugger standing there again, blinking at me, covered in dust. I absolutely flipped my gourd. He said his family didn’t have the money to feed another mouth so they sent him away, but this time the army wouldn’t have him, because we’d told them not to. I asked him why the hell he’d come back to the camp. You know what he said? ‘I liked the soda.’ That was the last time I ever buy a kid a coke, I’ll tell you that much.”

I asked Stuart if he honestly thought the kids would be better off without our intervention.

He shrugged. “It’s all shit, mate. You can’t stir it up without getting some on you is all.” Stuart rubbed out his cigarette on the side of his tin trailer and dropped it in an empty coffee can.

I asked him how he kept at his work when our intentions paved such roads as the boy had walked.

“I just keep looking on the bright side generally. There’s a new Dutch girl who moved to town recently. She’s quite fit, definitely worth a squirt, and her name’s a good omen. It’s Van der Cock.” Naughtiness splattered all over Stu’s face.

***

Walking to work was not doing the trick, so I started running. When he wasn’t talking about anticipated sexual conquests or his love of snow boarding, Stuart often mentioned how much he liked to jog, so I asked him if I could join after work.

I waited for him to change in the Palace’s dining hall where I had a burlesque view of his bare legs descending the staircase. They led up to a pair of day-glo orange nylon shorts slit right up the side to his pastel hips.

“Are you ready?”

Stuart adjusted the matching neon orange sweatband on his forehead. He looked like a roadwork sign with sneakers.

“Do you want to set the pace or follow?”

I told him I would try to keep ahead of him as long as I possibly could.

We made it down the bend from the Palace for about a kilometer without incident. Then Stuart inexplicably curved off the main road and cut through a refugee village. That’s when the heckling began.

“Kwadjo! Kwadjo!”

I told myself the refugees were just surprised at seeing two white men running in the late afternoon heat for no good reason, with no enraged mob at their heels. When rocks began whizzing past, it became clear that Stuart’s shorts had offended some conservative standards.

“That one almost hit my head!” Stuart called, delighted, and cut back onto a less inhabited path.

Vegetable plots and struggling fruit trees occupied the small fields to our right, construction projects for the warlords and nouveau-riche merchants sprung out to our left. A stream of sick-looking water poured from one of those developments into our path, pooling in parasite-breeding stagnation.

Something struggling in a bush caught my eye and slowed our pace. A bony Sudanese man draped in a red t-shirt and ragged pants pulled himself with terrible exertion on his belly out of the orchard he’d been lying in across the road until he could lower his face to the iridescent slick.

“Oh man,” Stuart murmured, “Don’t drink that.”

The man’s eyes flashed ferocious at us, but he did not try to rise. We ran past him in a wide berth. I asked Stuart what he thought was going on.

“Either sick or drunk I imagine. He didn’t look like a friendly cat to carry. Do you want to go back and talk him into going to the clinic with you?”

I did not, so we rounded the bend and the man was gone from sight.

More cat calls and shouts in Arabic and Dinka moved us on at a decent pace as we returned to the more inhabited sections of Juba, and finally back to the Palace.

“You up to go around again?”

Stuart jogged in place. His face turned pink from hard breathing and it clashed with his orange outfit. I decided to call it at just the one lap.

Back in my room, as I pulled off my heap of damp brown stains, I heard a child crying outside my window. The sound was uncommon only because of its persistence, growing in intensity for over the time it took to wash and change.

From the roof, leaning over the ledge, I could see at toddler sitting by the side of the road amid the thunder of trucks, motorcycles and scooters. The fingers of his one hand were hooked around his lower lip and his other arm was wrapped around his body. The child rolled his eyes up at every passerby and bleated a cry directly to them, no longer indiscriminately wasting his lungs at the whole of the world.

“Bah!… Bah!… Bah!”

He sounded like a baby goat who’d lost his mother, and he was ignored with the same ease of any other crying animal.

Some of the men and women living in the lean-tos down the road were out drawing their water for the evening and noticed me atop the Palace. Yells and gesticulations floated my way, indecipherable but unfriendly, so I slunk back. The child was still at his racket when Stuart returned.

I told him we should do something, that the child was only twenty feet away, that we couldn’t just ignore him and let him get run over. Stuart snapped, “Do what? Take him where? The mum could just be down in line at the well. Maybe none of the locals are doing anything because they know him. Do you really want them to watch two kwadjos walk out of their compound, cross the street and abduct a child? Do you think that would end well for us? Come on, come get a beer before dinner.”

The toddler’s crying rang fainter toward the end of the block and was out of our ears altogether when we sat down at the bar around the bend.

I told Stuart that I didn’t know how he kept at it, that he was right, the fucking kids. It was like watching the man beat the horse that drove Dostoyevsky insane.

Stuart rolled his shoulders and eyed our Kenyan waitress’s ass. “I’m not familiar with that.”

I explained I’d meant it was hard to watch.

“Ah, yes. Well, first of all, stop walking to work. That solves half your problem. Second, you’ve just got to have your goals, right? I figure I’ll be at this for at least two more years, and then I’m done.”

I asked if that was Stewart’s deal with himself, his self-appointed extraction date so he didn’t become a drop out to the world he’d come from.

“Well, that’s when I figure I’ll have enough put away to pay off the second house. One in Sweden and one in the UK; one for skiing, and one for the city. Then I can retire at 35, take a wife, all that. Maybe open a sporting goods store. Get back to snow boarding.”

I thought about it and decided I did not know what my limit was, but suspected I might have already passed it some time ago. I was curious to see what would happen next, the way one would about somebody else’s life or a television show.

The mystery of my role in this world was dispelled at least. There had never been a need for confusion, I was what I had always been; passive, observant, a witness who lacked the constitution for his task. In coming here to escape my nature I had only officiated it, been given permission. Something very bad would happen to me very soon as a result. I would make sure of that.

The child was gone when we returned though, and I was grateful.

Justin Hudnall graduated from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts by way of the Department of Dramatic Writing. He took a break from the arts for three years to pursue his other love, a career in emergency international aide work with the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF,) where he served in New York and Southern Sudan. He currently acts as Executive Director of So Say We All, a San Diego based non-profit arts collective.